Against the backdrop of the cost-of-living crisis, data highlights a worrying trend: CEO salary increases outstripping those of the wider workforce.

Salary remains the most tangible and relatable component of a CEO’s pay package. While annual bonuses or share-based awards often form the most significant components by size, salary is the component we can most effectively compare with the workforce. Salary is paid consistently, shapes living standards and, arguably, is the best reflection of how an employer values its staff.

Against the backdrop of the cost-of-living crisis, data collected by the Fair Reward Framework highlights a worrying trend: CEO salary increases outstripping those of the wider workforce. Of 88 FTSE100 firms, 13 (15%) increased the salary of their CEO to a greater degree than their workforce during the 2024 financial year. Across these firms, CEO salaries increased by an average 9.19% (median 9%), while workforce pay increased by an average of 4% (median 4%). This is a difference of roughly 5%. The workforce increase of 4% falls short of the rate of RPI over the same period, meaning many employees experienced real-term wage cuts while their CEOs pay grew healthily.

There has, however, been increased interest in this — both from a moral perspective that views such a trend as being fundamentally unjust, as well as from a more technical standpoint that highlights how such disparity is fundamentally harmful for business. This raises the question: why is this still happening?

For one, there simply isn’t a strong enough requirement on companies to explain why their CEOs salary has outpaced that of the workforce. Among the 13 companies, very little to no narrative was provided justifying this or outlining how it would impact internal firm disparities. HPC has long argued for a requirement on companies to explain the impacts their remuneration approach would have on such trends within annual reports.

A second reason lies in the structure of how CEO remuneration is determined in the first instance. Research has highlighted how RemCos are typically formed of a small set of non-executive directors who sit on multiple boards. Critics contend that this ensures an inherent bias as such individuals have historically benefited from, and are therefore predisposed to perpetuate, a culture of high executive compensation. Resultingly, it is in their own interest to sustain inflated executive pay. Whilst it is challenging to prove that there is a conscious bias at play, at the very least it is undeniable that such individuals are accustomed to an environment in which high pay is the norm.

Some have argued that substantial CEO pay awards are needed to attract and retain key talent. This speaks volumes to how one side of the corporate narrative often frames employee wage restraint as cost control, while assuming that CEOs are scarce assets. Not only is this especially pertinent given that the link between executive performance and pay outcomes is weak, but also because the assumption that only a small number of individuals are capable of leading large firms is both misguided and dismissive of the capable talent already within companies.

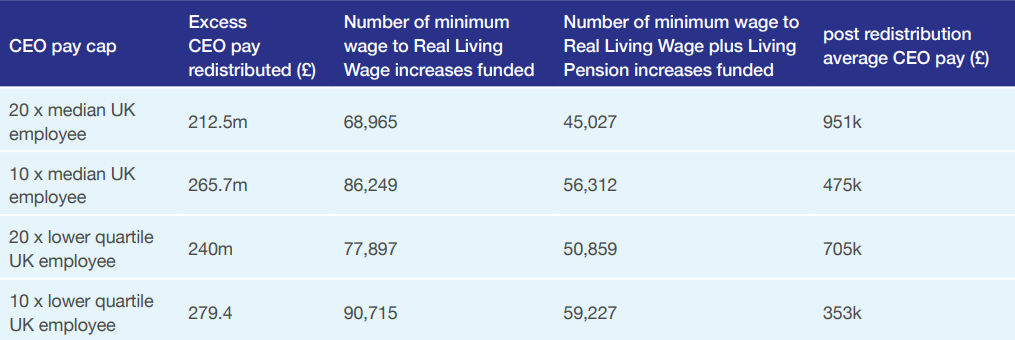

These arguments all centre on what constitutes an effective use of corporate funds. Research shows that pronounced pay gaps can negatively impact employee morale, leading to reduced productivity and increased job turnover rates. These outcomes fundamentally undermine any firm seeking to enhance its profitability and shareholder returns. Excessive executive compensation can also divert finite corporate capital away from areas where it could have significant positive impact: the graphic below illustrates the potential for redistribution if CEO pay at non-living wage accredited companies was capped at various multiples of their median UK employee pay.

Under the most drastic of the four examples, capping CEO pay at ten times that of their median worker would be sufficient to raise the annual pay of over 91,000 full time workers earning the National Living Wage to the Real Living Wage. This would still leave CEOs with an average yearly pay of £353k, comfortably over double the amount needed to qualify for the top 1% of earners in the UK.

A number of policy ideas have been suggested to prevent such imbalances from developing and ensure that corporate wealth is being used effectively. At the more technical end of the spectrum is the idea of a ‘wage lock’. Thus far, this has focused on the idea that companies should be prohibited from paying out dividends to shareholders or engaging in share buybacks unless employee pay has kept pace with inflation. This principle could be expanded to include executive pay, stipulating that any increase to CEO salary must be preceded by inflation-linked pay rises to the workforce as a minimum. This would go one step toward tying reward to fairness, while also compelling RemCos to consider their justifications for large CEO salary increases and to better balance internal equity considerations with external peer benchmarking exercises when determining CEO pay.

A number of policy ideas have been suggested to prevent such imbalances from developing and ensure that corporate wealth is being used effectively. At the more technical end of the spectrum is the idea of a ‘wage lock’. Thus far, this has focused on the idea that companies should be prohibited from paying out dividends to shareholders or engaging in share buybacks unless employee pay has kept pace with inflation. This principle could be expanded to include executive pay, stipulating that any increase to CEO salary must be preceded by inflation-linked pay rises to the workforce as a minimum. This would go one step toward tying reward to fairness, while also compelling RemCos to consider their justifications for large CEO salary increases and to better balance internal equity considerations with external peer benchmarking exercises when determining CEO pay.

Despite practical challenges surrounding its implementation, HPC has advocated for a maximum pay-ratio cap whereby a CEO would be restricted from earning more than a certain multiple of their median employee pay. This article has already highlighted the transformative impact this could have on the pay of thousands of low-earners across the UK. While this may appear radical, it is worth recalling that David Cameron called for a maximum wage ratio cap of 20:1 for public sector bosses in 2010. An HPC survey also found that 49% of survey respondents believe CEOs should be paid no more than ten times their middle and low earning colleagues, while 62% felt it should be no more than 20 times, indicating the strong public support this policy could enjoy.

These measures would help rebalance corporate pay structures in the interests of employees, signalling a broader shift toward valuing the workforce who form the foundation of company success as much as the individuals who lead it.