Blog by HPC Director Luke Hildyard on the new edition of the Corporate Governance Code, regulating the boards of Britain’s biggest companies.

The UK Corporate Governance Code, and why it matters

The UK Corporate Governance Code, which sets out governance and reporting standards for Britain’s biggest companies, tends not to attract much attention beyond those with a niche interest in the topic. It’s issued by technocrats at the Financial Reporting Council, an independent regulator, with only indirect input from politicians, and it isn’t even legally binding. The Code is reviewed and updated every few years, and operates on a ‘comply or explain’ basis meaning that boards don’t necessarily have to comply with its provisions, as long as they explain why they chose not to, in their annual report.

But corporate governance practices shape business operations that have a big impact on our lives as employees and customers of those businesses, and citizens of the communities where they’re based. While compliance with the Code is voluntary, it’s taken very seriously by boards and investors. The provisions range from specific measures designed to ensure the probity and accountability of corporate boards, like recommendations for a majority of directors to be independent and limits to the number of directorships at different companies that they can accept. Or more general responsibilities, often with a vaguely progressive flavour, such as the provisions encouraging a transparent appointments policy, a corporate culture aligned with the organisation’s values and purpose or the use of internal pay gaps as benchmarks when setting executive pay.

Shareholders use the Code as the yardstick against which to judge the governance of their investee companies, so are keen to see its provisions applied. This means that compliance quickly takes on considerable importance to company directors. In practice, any measures that appear in the Code are likely to be widely, if not universally, adopted by large numbers of influential British businesses, even though they don’t technically have to do so.

The backlash against ESG and stakeholder capitalism

For this reason, the latest edition of the Code, published last week was something of a disappointment. The original draft, issued for consultation last Autumn, included a number of references to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues, stating that companies should report on how these factors effect business strategy; explain how measurement of environmental and social performance is assured; and link executive pay outcomes to ESG objectives. These were pretty tame measures, but would have at least made issues like pay and employment practices, supply chain ethics or greenhouse gas emissions more visible at boardroom level. The code is heavily influenced by the views of businesses and investors themselves. So the inclusion of these kind of provisions in the draft version probably reflects the recent interest in a ‘purposeful’ or ‘stakeholder-oriented’ form of capitalism, with many advocates in the business community, that recognises the need for business practice to align with the interests of wider society, and for business leaders to make balanced judgements when short-term profit maximisation comes into conflict with social or environmental considerations.

Unfortunately, when the final version of the Code was produced, all these provisions had been deleted. This represents a victory for a very different strand of business opinion that sees high governance standards and the so-called ‘reporting burden’ as a cause of the UK’s economic malaise. It suggests that efforts to denigrate environmentally and socially conscious business are becoming increasingly effective. In the US this has been a populist, culture war project pushed by nationalist politicians and activists, with ESG usually grouped alongside ‘Diversity, Equity and Inclusion’ (DEI) initiatives as part of a conspiracy by ‘woke business’ to push a particular social agenda. In the UK it’s been more of a traditional right wing economic argument aimed at technocrats and practitioners. Recent examples include City grandees arguing that curbs on executive pay and concern over CEO to worker pay gaps are holding back the UK economy, leading fund managers criticising Unilever (probably the major UK business most engaged with ‘stakeholder capitalism’) for being too focused on sustainability at the expense of shareholder value, and Conservative politicians criticising ESG investors divesting from arms manufacturers for harming key UK companies. Worryingly, progressive voices in the business and investment world are already suggesting privately that as these sentiments become more in vogue relative to stakeholder-oriented capitalism, internal business practice and decision-making is changing accordingly.

Next steps for policymakers

While nobody should be under the illusion that ESG-sensitive business and voluntary measures undertaken under the banner of ‘stakeholder-oriented capitalism’ are any kind of substitute for proper regulation of big business and corporate power, left criticisms of these concepts are entirely incidental to the abandonment of the provisions in the draft Corporate Governance Code. The de-regulatory arguments from the political right are obviously having much more impact. Furthermore, there are obvious challenges associated with penalising every pernicious business activity. Measures directing business leaders to understand and measure their social and environmental impact and to generally act in a manner consistent with the societal interest are a necessary complement not a substitute for laws and regulations prohibiting or incentivising specific business practices. As such, the changes to the draft Code are a real pity.

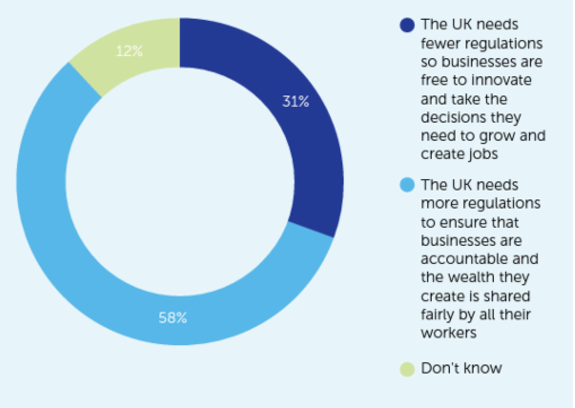

There is also the risk that the increased business scepticism of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ and the emerging campaign against it will filter through to politicians who tend to take their cue on economic policy from business leaders fairly uncritically. More optimistically, however, there are good grounds to think that this campaign is badly at odds with wider public opinion. Polling repeatedly shows a majority of respondents in agreement with the notion of business having responsibilities to their workers, wider society and the environment beyond just making a profit for shareholders. When the High Pay Centre polled on the topic, almost twice as many people said that more business regulations would be better for UK living standards as said fewer.

The limited adjustments to the Code also create space for the next Government to undertake a fuller review post-election of the UK’s reporting and governance arrangements, covering both the Code and wider laws and regulations. This could incorporate more focused disclosure requirements covering areas like pay levels across the workforce, including indirectly employed workers; relations with trade unions; and the conception and measurement of the organisation’s social and environmental impact. It could also cover stronger worker voice at board level and measures to ensure more participatory, democratic business decision-making that disperses power over large and powerful businesses beyond a handful of super rich executives and investors to their thousands of workers and other stakeholders across the world. This need not be seen as ‘anti-business.’ Many of the most successful companies are already doing these things – and they are far more in keeping with public sentiment and the spirit of our less deferential, more connected society than the removal of the forward-thinking provisions contained in the draft version of the Code.

In a world that needs to meet urgent environmental and social challenges – where businesses need to show they are part of the solution or at least not part of the problem – a regulatory regime that effectively provides this accreditation for British companies would be an asset not a hindrance. In an era of low productivity, yawning inequality and a looming environmental crisis, the economic lever we should be reaching for is one that raises governance and reporting standards rather than lowering them.

(To read HPC’s response to the consultation on the revisions to the Corporate Governance Code, click here)