New polling shows strong support for caps on top pay and measures to tackle inequality

As part of a forthcoming report on pay ratios, we recently conducted some opinion polling on public attitudes to pay inequality and its consequences.

The results were really interesting, revealing strong levels of public disapproval for current CEO worker pay gaps, and a sense that how wealth and prosperity in the economy are distributed matter more for people’s living standards than just the headline level of economic growth.

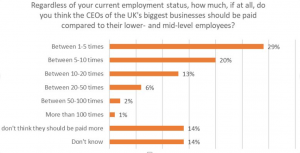

We firstly asked survey participants what CEOs of the UK’s biggest companies should be paid compared to their middle and low-earning employees. 62% said no more than 10 times would be appropriate. Just 3% said over 50 times.

The median pay ratio between a FTSE 350 CEO and their median employee (on a full-time equivalent basis) was 53:1 in 2020. 21% of companies paid their CEO more than 100 times their median employee. Businesses shouldn’t be run according to public opinion, but they do have to recognise the values and serve the interests of the societies that they’re situated in.

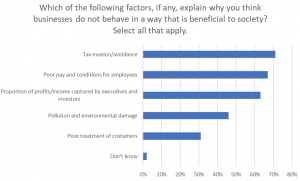

One of our follow up questions suggested that they are not currently doing so. More respondents (49%) said that business behaves in a way that is generally harmful to society than said they behave in a way that is generally beneficial (38%). Of those, who said that they felt business did more harm than good, poor treatment of employees and excessive rewards for executives and investors were two of the three most popular reasons why, behind tax evasion and avoidance.

Companies disclose ‘risk registers’ in their annual reports, but a sudden public backlash against perceived anti-social business practices is rarely included amongst them. More in-depth focus groups reveal public attitudes to business, the economy and issues like taxation or inequality are complicated and sometimes contradictory. As much as people take a deeply cynical view of the business elite, they’re equally sceptical of the motivates and capability of anyone seeking any kind of change.

So perhaps boards are right not to worry too much that their pay, employment and tax practices will imminently bring about the downfall of capitalism. Nonetheless, our findings do suggest that business leaders (and the policymakers that regulate them) shouldn’t be dismissive of the low-standing in which they’re held, and should recognise the significant risks that derive from it.

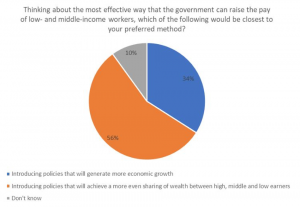

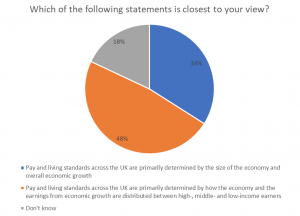

The other interesting insight revealed by the polling was that a majority of respondents (53%) said policies that share wealth more evenly would be much more likely than those aimed at lifting economic growth (34%) to raise incomes and living standards for those in the middle and at the bottom. A larger number people (49%) felt that at a more general level, living standards are determined by the way resources are distributed rather than the headline growth rate (34%).

In practice, it has historically been a mixture of growth, through innovations and advancement in technology or medicine for example, and measures such as trade unions, progressive taxation and minimum wages ensuring that the proceeds of growth are shared fairly that have raised living standards. It is also perfectly feasible for measures designed to share incomes and wealth more evenly to also result in greater economic growth.

But it is very hard to imagine any mainstream politician or commentator dedicating to fairer wealth redistribution anything like the energy that they expend in search of greater economic growth.

This hasn’t stopped the last fifteen years being one of the most miserable periods on record for UK economic growth. It just means that in the throes of a ‘cost-of-living crisis’, we get fairly risible solutions, like extending MOT renewal deadlines, rather than more meaningful redistributive policies like compulsory profit sharing, expanded trade union rights or a maximum CEO:media worker pay ratio of something like 10:1.

Our polling suggests that this outlook isn’t just close-minded, unambitious and ineffective in terms of the impact on living standards, it’s also deeply at odds with public opinion.